Corruption Remains under Control

Singapore’s founding fathers recognised that one of the key factors for Singapore’s survival and success is eradicating corruption. Five decades on, Singapore has become widely acknowledged as one of the world’s least corrupt countries. The Corruption Perceptions Index 2015 ranks Singapore as the 8th least corrupt country in the world and the least corrupt Asian country. Singapore is also ranked first in the 2015 annual survey, conducted by the Political and Economic Risk Consultancy (PERC), on corruption in 14 Asian countries, Australia and the United States.

2. We continue to see a low incidence of corruption in Singapore today. Strong political will and leadership, constant vigilance by the CPIB, an independent judiciary and a responsive public service continue to keep corruption in check. Our founding Prime Minister, the late Mr Lee Kuan Yew once said “We have succeeded in keeping Singapore clean and corruption free. This requires strong political will, constant vigilance and relentless efforts by CPIB to follow up every complaint and every clue of wrongdoing.” The clean system we have put in place in Singapore should never be taken for granted. The government and our citizens must work together to continue this legacy.

Corruption cases registered reached a new low despite more complaints lodged

3. In 2015, CPIB received 877 complaints, a 19% increase from the 30-year low of 736 complaints received in 2014 (Figure 1). On the other hand, the number of cases registered for investigation continued its downward trend for the last 3 decades. In 2015, 132 cases out of the 877 complaints received were registered for investigation by CPIB, a 3% decrease from the 136 cases registered in 2014.

4. The complaints received by the CPIB comprised both corruption-related and non-corruption-related type of information, the latter of which would be referred to the relevant government authorities for their action. The quality of the corruption complaints received directly affects the number of cases that the CPIB registers for investigation as complaints that lack details or provide only vague or unsubstantiated information, often cannot be pursued. It is therefore critical that the complainants provide sufficient information such as where, when, how and who were involved in the alleged corrupt act.

Figure 1: No of Complaints Received by CPIB vs No of Cases Registered for Investigation

Corruption complaints lodged in person remains the most effective mode

5. The majority (35%) of complaints received by the CPIB in 2015 were made through mail or fax, but these only accounted for 13% of investigations. In comparison, only 8% of complaints were lodged in-person, but these accounted for 31% of investigations. Complaints lodged in-person are more effective because CPIB can obtain further details more readily. The second most effective mode was complaints through phone (17%) (Figure 2).

6. The CPIB takes a serious view of all complaints or information that may disclose any offence under the Prevention of Corruption Act. The Complaints Evaluation Committee (CEC) comprising members of the CPIB Directorate will deliberate on each complaint and ascertain whether there is sufficient information to warrant a criminal investigation or other follow-up action. All complaints are deliberated upon in the same way regardless of the nature or amount of the gratification, or whether the complainant has identified himself or chosen to remain anonymous.

Figure 2: Modes of Complaints Received vs Complaints Resulted in Investigation in 2015

Private sector cases make up majority of corruption cases in Singapore

7. Private sector cases continued to form the majority (89%) of all the cases registered for investigation by the CPIB, a 4% point increase from 2014. Most of these cases involved private individuals giving, offering or receiving bribes. Of the private sector cases, 13% involved public sector employees rejecting bribes offered by private individuals (Figure 3).

8. In comparison, public sector cases have been declining since 2013. In 2015, public sector corruption cases accounted for 11% of all registered cases for investigation in 2015, a drop of 4% points as compared to 2014.

Figure 3: Breakdown of the Cases Registered for Investigation by Private vs Public Sector

Higher clearance rate despite increase in workload in 2015

9. In 2015, the CPIB handled a total of 678 cases. This comprised 132 new cases registered from complaints lodged in the year, 423 new cases registered in the course of investigations and 123 uncompleted cases brought forward from 2014. This is the highest number of cases handled by the CPIB in the last 3 years (Figure 4).

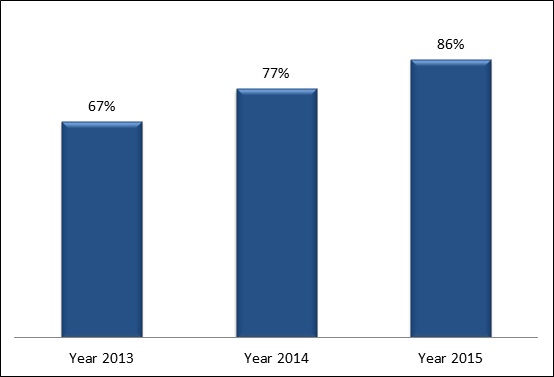

10. The CPIB achieves a high clearance rate of its cases annually. In 2015, despite an increase in the number of cases handled, the clearance rate (86%) increased by 9% points over 2014 (77%). This is the highest clearance rate in the last 3 years (Figure 5).

Figure 4: No of Cases Handled in a Year

Figure 5: Yearly Clearance Rate

No syndicated corruption in Singapore

Private sector employees formed majority of persons prosecuted in court

11. Most corruption cases were opportunistic in nature, brought on by the greed of individuals who exploited loopholes in their organisation’s work processes. The total number of individuals prosecuted for corruption offences remains low. In 2015, 120 individuals were prosecuted in Court for offences investigated by the CPIB. Besides corruption offences, the CPIB will also investigate non-corruption offences uncovered in the course of investigations.

12. In terms of persons prosecuted in court for corruption-related and non-corruption offences, the percentage of private sector employees remained fairly stable, averaging 90% over the past 3 years. Correspondingly, the number of public sector employees prosecuted remained low at average of 10% for the last 3 years (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Public and Private Sector Employees Prosecuted in Court

13. Based on the cases of private sector employees prosecuted in Court for corruption-related offences in 2015, three main areas of concern were noted:

i. Construction (e.g. building construction, addition and alteration works, renovation);

ii. Marine services (e.g. bunkering, shipping, shipyard works); and

iii. Procurement (e.g. purchase and sale of equipment, construction materials, food & beverages).

Cases in brief are appended (Annex A).

High conviction rate for CPIB cases

14. The CPIB will investigate any corruption-related cases thoroughly, regardless of the nature of the offence or bribe amount. The effort and firm commitment by the Bureau and the Attorney-General’s Chambers has contributed to a high conviction rate for corruption-related cases over the years. In 2015, the conviction rate was 97% while the average conviction rate for the past 3 years has remained consistently above 95% (refer to table below).

15. Under the Prevention of Corruption Act (PCA), any person convicted of an offence is liable to a fine of up to $100,000, imprisonment for up to five years, or both. Where the offence involves a government contract or bribery of a Member of Parliament, imprisonment may be extended to seven years.

| Year | Conviction Rate (%) |

| 2013 | 97% |

| 2014 | 96% |

| 2015 | 97% |

More initiatives and publicity in the battle against corruption

16. In addition to enforcement, the CPIB continues to educate the public through community outreach efforts and prevention talks to heighten awareness on corruption matters. Regular publicity of individuals prosecuted for corruption offences also serves a deterrent effect.

17. As part of our outreach programme, the CPIB has organised a roving exhibition with the theme “Declassified – Corruption Matters”. It will be launched at the National Library on 7 April 2016, before roving to other regional libraries. The exhibition will highlight the CPIB’s history, selected cases and the personal experiences of CPIB officers.

18. CPIB’s Corruption Reporting Centre will open in December 2016. Located centrally at Whitley Road, near Stevens MRT station (Downtown Line 2), it will make it more convenient for the public to walk-in and report suspected corrupt practices. This is part of CPIB’s efforts to encourage members of the public to step forward and report corruption. The public can also continue to reach us through the following channels:

i. Walk-in to the CPIB at 2 Lengkok Bahru, Singapore 159047;

ii. Call us on our 24-hour hotline at 1800-376-0000; or

iii. Lodge an online complaint at www.cpib.gov.sg.

Private sector engagement

19. The bulk of corruption cases in Singapore continue to come from the private sector. The CPIB will engage the industry players and business communities to educate private sector employees. The CPIB is the National Convenor on the standards development of the ISO 37001 on Anti-Bribery Systems. CPIB leads a working group, comprising representatives from trade associations, industry players and businesses, to formulate national viewpoints and consult stakeholders on the implementation of the international standard. This will aid private sector companies in establishing processes and systems to prevent corruption and promote ethical business culture.

20. With the implementation of the ISO 37001 standard later this year, the CPIB is developing an integrity package to help businesses weed out and combat corruption. Business owners can use the package to learn more about corruption issues and how to implement a practical, integrity-based framework in their company.

21. Meanwhile, companies can source for readily available materials such as guidelines and measures which they can adopt to minimise risks of corruption at the workplace. For instance, Transparency International develops private sector tools that reduce the opportunities for corruption and enhance the ability of people and organisations to resist it. Some of these tools provide frameworks for companies to develop anti-bribery programmes.

Battling corruption together

22. With an increasingly complex operating terrain, the battle against corruption will only get tougher. The transnational nature of corruption also means that Singapore must cooperate with other countries to combat corruption, and cannot work in isolation. Together with the global community and its international partners, the CPIB will strive to explore new and effective ways to fight corruption both on the domestic and global fronts.

23. Singapore’s clean reputation of integrity and incorruptibility was forged by our forefathers who had the will and determination to transform Singapore in one generation. CPIB will work together with the community to uphold the high standards we have achieved, and safeguard our nation’s integrity.

Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau

Annex A

Construction

Abdul Jalil and Md Nurul Islam, construction supervisors of Everlast Industries (S) Pte Ltd, were assigned to the work-site at Ng Teng Fong General Hospital to oversee the installation and painting of handrails by their sub-contractor, FM Construction Pte Ltd. The two would have to certify on the progress report for the work done for the installation and painting works by FM Construction before the sub-contractor could receive any payments from Everlast Industries (S) Pte Ltd. On 5 May 2015, both pleaded guilty to attempting to obtain a gratification of $2,000 from FM Construction Pte Ltd, in return for providing the necessary certification. They were sentenced to three weeks’ imprisonment each.

Marine services

Yu Lu, a chief engineer of Cara Shipping Pte Ltd, was responsible for the safe navigation of the vessel Stella Ada, by ensuring that the major machineries and equipment on board the vessel are functioning properly and the vessel has enough bunker fuel. On the other hand, Han Xingshi, a Technical Superintendent of Stella Ship Management Pte Ltd, provided maintenance for the vessels managed by Stella Ship Management Pte Ltd, such as the repairs of equipment and spare parts etc. Stella Ship Management Pte Ltd was tasked by vessel owner, Cara Shipping Pte Ltd, to maintain their ships. Both Yu and Han then struck a deal to misappropriate the marine fuel oil from the Stella Ada while the vessel was under their care. They tampered with the fuel gauge to reflect a higher level so as to cover up the shortage of fuel oil, and tried to bribe Lou Jinjin, the Operations Manager of Cara Shipping Pte Ltd with RMB$20,000, when he came aboard to carry out the inspection checks. On 16 March 2015, Yu Lu* and Han Xingshi* were found guilty and sentenced to five weeks and six weeks imprisonment respectively for corruption.

Yu Lu and Han Xingshi were also sentenced to 6 months and 5 months imprisonment respectively for criminal breach of trust.

Procurement

Lam Wah Hing, a sales representative at switchboard supplier Elsteel Techno (S) Pte Ltd, was responsible for obtaining sales for Elsteel. Sometime in late 2012, Saw Kiat Siong, an engineer with the Malaysian based company Rutherford Global Power Production Sdn Bhd, approached Lam to ask him for a quotation for seven switchboards that Rutherford required. Lam, however, did not provide a quotation from Elsteel Techno (S) Pte Ltd,. Instead, he approached Ivan Yeo Eng Choon, a Director at 3 Ace Systems Pte Ltd, Elsteel Techno (S) Pte Ltd’s competitor, to provide a quotation. Lam then worked out an agreement with Yeo that he should pay Lam 10% of the contract value and Saw 5% in return for helping 3 Ace Systems Pte Ltd to secure the contract with Rutherford Global Power Production Sdn Bhd. This resulted in Rutherford Global Power Production Sdn Bhd placing an order for two switchboards worth a total of $90,500 from 3 Ace Systems Pte Ltd. In total, Lam received $13,573 from Yeo, of which $700 was given to Saw for his help. Lam Wah Hing was sentenced to 4 weeks’ imprisonment and ordered to pay a penalty of $12,873 while Saw Kiat Siong was fined $4,500 and ordered to pay a penalty of $1,000. Ivan Yeo Eng Choon’s case is still before the Courts.